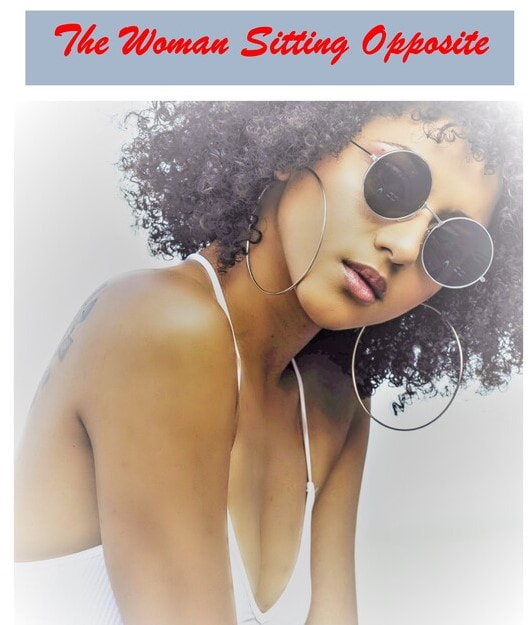

Showcase: A tale of lust, deceit and payback!

This is The Woman Sitting Opposite, from my collection 20 Stories High, published by Armley Press. The paperback version is £8.99 from Waterstones, WH Smith and all top bookshops.

ISBN: 978-0-9934811-8-5

If you wish to order from Amazon, please click here.

ISBN: 978-0-9934811-8-5

If you wish to order from Amazon, please click here.

The Woman Sitting Opposite

THE WOMAN SITTING OPPOSITE with the gold hoop earrings put her hand on his hand. Luke saw a suntanned face, lustrous black hair, white even teeth. Maybe early forties – ten years older than himself. She said: “I know you from somewhere.”

She reminded him of Caroline, a graduate student he’d got close to last year. He said: “Gosh, I’m sure I’d remember.”

The woman wore a floral dress that left the tops of her breasts bare. She continued to press his hand, look unblinking into his face. He squirmed on one of those uncomfortable wooden chairs that Emma, wife of the head of English, had put out for her garden party.

The woman said: “You’re married. I can feel the ring. Very smooth. Very hard.” She took her hand away, smiled at him with fine brown eyes.

He said: “Are you a wife? I mean are you married to...” What should he say? One of the myriad academics swarming over Emma’s lawn, waving glasses of Merlot?

She held up her ring finger. “Yes, I am. Married.” He noted the full stop in the middle. “But not to anybody here.” She picked up her wine glass, drained it, stood up. The dress finished just above a nice pair of knees. Nice! Was that the best word a poetry tutor could think of?

“Goodbye.” She walked across the lawn.

Out of my life, he thought. He looked at his watch. Marianne would be back from work by now and he had to pick up the stuff from Tesco. He looked down at the table top. Only then did he notice the earring.

When he got home, Marianne was brewing coffee in the kitchen. She had changed into her tee-shirt and jeans and was reading The Guardian. He poured himself a cup.

“Get everything?” she asked. She was tall, slender, blonde, with an elfin haircut.

“Mini-pizzas, rocket, spinach, tomatoes, peppers, potatoes for the baking thereof.”

“Can you get on with it? I’ve got a report to do for Andy. If I get it finished tonight, it will leave the weekend clear.”

“Right.”

“Except I have to deliver it.”

“Can’t it be e-mailed?”

“It’s not just the report. Andy and I have to talk. You wouldn’t believe the state of the housing market. We might have to give a couple of people the push. Well, he might. He’s the boss. But he’s asking my advice. Tough decision. Fast action. Deliver the blow. First thing Monday morning.”

Luke turned the oven to 200, unpacked the mini-pizzas, stuck the potatoes on metal spikes, waited five minutes, drummed his fingers on the worktop.

“Right,” said Marianne, “I’ll start that report. And I’ll check out our e-mails.” She went upstairs to the room they used as an office.

When he’d put the potatoes in, Luke took out the earring. He’d been minded to call the woman. But he didn’t know her name. It would mean phoning Emma and Phil, head of English. They’d say “Drop it off with us and we’ll see she gets it”.

He checked the potatoes, skim-read The Guardian. His mobile rang.

She said: “You’ve got something that belongs to me.”

“How,” he said, “did you get my number?” Then: “Hang on a minute.” He took out the potatoes, moved them to the bottom of the oven, shoved the mini-pizzas in. “We’re having mini-pizzas,” he said.

“How nice. I’ll tell you how I got your number when I see you tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow?”

“The day after today. Saturday, if you’re still not sure. I’m sure you can find a reason to be away for a bit. Popping down the B&Q for a couple of brackets. Give me a call when you’ve set off.”

He thought about Marianne delivering the report to Andy. “OK. Where shall we meet?”

“It’s a mystery tour. Perhaps you’ll get a reward at the end of it.” She laughed and added: “Do you know a pub called the Duke of York?”

When she rang off, he mixed the salad. Later he thought: How did she know I’d pick up the earring?

They met outside The Duke of York, scarcely ever used by university people. She wore a powder-blue trouser suit that showed off her figure.

“No earrings today?” He handed it over.

She put it on. “Now I don’t feel naked.” She bent her arm and poked his arm through it.

Inside, she asked for a gin and tonic and he ordered a half of pale ale. He selected the table in the far corner where there wasn’t much light.

“I’m Jayne. With a y. And you’re Luke.”

“Hello, Jayne with a y.”

“And I do know you from somewhere and I’m hurt you don’t remember. We were both at the protest meeting against the closure of the chapel. When the bursar said it was a matter of replacing a Gothic design that was merely attractive with a modern design that was practical, you accused him of being full of high sentence but a bit obtuse. I liked that.”

“It’s TS Eliot.”

“I know it’s TS Eliot. But I didn’t know you. So I asked around, said I was forming a committee to combat the obtuse.”

He laughed.

“Good,” said Jayne, “you’re starting to relax. Now I’ll tell you how I got your mobile number. Just so you won’t worry your pretty little head. I told Phil, your head of department, that Keiron wanted to do an interdepartmental project involving poetry and therapy. And Keiron thought you were the man to handle it. Phil was delighted.”

“Who’s Keiron?”

“Professor Keiron Cannadine.”

“The head of psychology? Is he your boss?”

“He’s my husband.”

Luke wiped up his spilled drink with a beer mat. “And what happens when Keiron finds out?”

“Oh, I tell him everything. He’s not the jealous type. Anyway, he’s gay. It will come to him as a great relief if I’m otherwise occupied.”

“My wife. Marianne. She’s not a lesbian.”

“No. I’m sure she’s not.”

“I mean she must never know.”

“I’m very discreet. And so is Keiron.”

“Do you think you should be telling me about him being gay? Isn’t that a bit intrusive?”

“Not as intrusive as you fucking his wife.”

She wrote her private e-mail address on a beermat and he did the same. She said: “This Marianne, she doesn’t give you enough, does she?”

“Enough of what?”

"Whatever it is you want.”

The Cannadines had what Jayne called a chalet in a park outside town, overlooking the beach. It was a caravan with the wheels removed among a litter of thirty such vehicles. There were two rooms with pull-down beds; a TV and a Digi box; a kitchenette with cooker, sink and fridge; a flush toilet; and a shower which could not be used while someone was using the toilet. Jayne said: “It’s only thirty minutes’ drive from home. Keiron’s job gives him so much spare time and he uses the chalet to entertain his boyfriends. So I do the same with mine.”

They organised a schedule based on Luke having Tuesday and Wednesday afternoons away from campus to research his doctorate on “Socialist Tendencies in Restoration Drama”. Luke was nervous. He worried whether even the most affable gay man might not fly into a fit of pique over a wife’s brazen infidelity. He wondered how to cope if they were interrupted in flagrante. He would make sure his Renault Clio always had the petrol topped up. Also, he considered what clothes could be removed and put back with minimum of fuss, preferring a simple tee-shirt over anything with buttons. And he bought himself a pair of trainers with Velcro fastenings, though he really preferred laces.

It had been some time since he’d bought Durex. Was it better to go to Boots (very public) or use the machine in the gents (which looked untrustworthy)? In the end he drove to an out-of-town superstore called Drug City, only to discover the smallest number of rubbers he could buy was 18, a fact that caused Jayne some hilarity.

That first time went OK. Using his Satnav, Luke found the park easily. Jayne was welcoming and provided a glass of Shiraz. The Velcro on the shoes proved speedy. The pull-down bed, though narrow, was more comfortable than many he’d shared with Marianne in their pre-marital days. And Jayne naked was everything her floral dress had promised. Afterwards, she said: “There. That wasn’t so bad.” She patted his head.

Luke brushed a hand across his parting. “What will you tell Professor Cannadine?” He had never met Jayne’s husband and didn’t like to refer to him by his first name.

“I shall tell him just that. It wasn’t so bad.”

The TV was showing John Wayne in Red River. Luke liked films in general and westerns in particular – he liked their dangerous situations. So they stayed to watch it.

Her e-mail later said: I told Keiron I’m forced to do it at least 17 more times and he was most amused. He is pleased to see how happy I am.

The second time, two weeks later, they tried a new position, Jayne on her side and Luke at the back – and Luke failed to come. When he realised it wasn’t going to happen, he grunted ecstatically, slowed down his thrusting, sighed loudly and pulled out.

This time there was no western. Jayne got some Sauvignon from the fridge. “We should talk,” she said.

“OK.” He waited.

“I’m not just a good fuck, you know. Though I am a good fuck. I’m also a woman. I have needs. Emotional needs.” A pause. “Of course, I need sex like anybody else. And I don’t get it from Keiron anymore. But I also need someone to comfort me. To be my friend.”

Luke got up from the bed, put on his underpants, put his arm round her. “I’m good at friendship.”

“I’ve been unlucky with men. Just like my mother. My father left her, you know. And she pined away and died. Still, one shouldn’t mull over these things.”

Her e-mail said: Cool Hand Lukey really made my day. Now she knew he was a film buff, she liked to make the odd movie reference.

The third time, he again failed to come. But Jayne managed her own noisy orgasm so his previous pantomime was unnecessary. “Wow!” she said afterwards.

They sipped more Sauvignon. He said: “Did you know” – he still hesitated over the name – “Keiron was gay before you married him?”

“I knew he’d had flings. I thought all English boys did that. Public school, et cetera. I’m half French, you see. My mother’s side. And I lived in France when I was a child. So I’ve never been too sure about English ways. Mon Dieu!” she added with a giggle. She finished her drink and poured another.

“I think it’s a class thing,” said Luke, to let her know some English ways were not his.

“I’m philosophical about it. Some of it’s been quite an experience. Sometimes Keiron liked to take me along, you know. Sometimes we’d do sandwiches…”

Luke had a confused mental image of a table prepared for tea. Then…

“Keiron would do me from the back while the boyfriend had me from what you might call the forward position. Then, if they had any energy left, they’d do turnabout. I hope I haven’t shocked you.”

“Shocked? No, no.” When she offered him another glass, he said: “I’m driving. And so are you.”

Her e-mail said: Wow! Gosh! Do keep it up! No pun intended! Luke had been reading a newspaper story about how detectives retrieved deleted e-mails. But he pressed the delete button anyway.

The fourth time, he entered her OK, but within minutes felt himself losing it. Jayne shouted: “Stay inside!” She writhed, fiercely but mechanically, then subsided. “Ah well,” she said, clutching his hand, “every man has a no-show now and again. C’est la guerre.” Now she had revealed her French parentage, Jayne enjoyed the occasional linguistic sortie.

They got up and looked in the fridge but there was only a pork pie and a bottle of Lucozade Sport. “That’s Keiron for you. He empties the fridge with his little friend. That’s so selfish. Don’t you think? Well, two can play at that!” She threw the pie at the window. Splat! Then she threw the Lucozade, but it bounced and fell. “Aagghh!” she yelled. “Screw you, Keiron!”

“It’s a plastic bottle.” Luke dropped it in the waste bin and picked up the bits of pie with some kitchen roll.

“One day I’m going to kill that bastard!” she said. Then in a quieter voice: “He’s a darling, of course. But he can be selfish. Unthinking. He’s the one who gave me syphilis.”

Luke sat down on the bed.

“Don’t worry. It’s all gone now. But it upset me. The thoughtlessness. You can understand that, can’t you? You’re an understanding person.”

And her next e-mail said: Don’t little Lukey worry bout his little blip. Jayne expecting return of Tarzan soon.

Next time he saw her, it was in the street. He was coming out of M&S with a pair of Blue Harbour jeans. She was being escorted back inside by two uniformed women, one thin, one fat. She was saying: “I thought I’d paid.” Her voice was slurred. The fat woman carried a small black dress with lace at the sleeves.

“Jayne!” he said.

She stared at him.

“Do you know this woman?” asked the thin one.

“Yes. What’s the trouble?”

“They think I’m a thief.” Jayne took out a hankie and started to cry. “I thought we’d paid.”

Luke thought fast. “I can see,” he said, “where the mistake might have arisen. We were separated. I told her…”

“That you had paid?” said the fat one.

“That I was going to pay.”

“Going to pay?” The women looked at each other.

“She may have misheard me. It may have sounded as if I’d already paid. Look.” He held up his M&S bag, opened it to reveal the jeans. He took the receipt from his wallet. “I paid for the jeans, you see. She may have thought I’d paid for both.”

“She doesn’t have a bag,” said the thin one.

“I didn’t want one,” said Jayne, “I hate those fucking bags. They can’t be recycled. And I don’t believe in landfill.” And then she went stiff, vomited, and fell over.

“Better call a doctor,” said Luke.

Instead, they called the lighting department’s qualified first aider, a man with steel-rimmed glasses. “She’s drunk a bit too much,” he said after washing her face and the front of her jacket with a flannel and applying a plaster to her cheek. Jayne sat on a high-backed chair surrounded by lights and lampshades. “You’ve drunk a bit too much, haven’t you, madam?”

Jayne nodded. She began to suck her thumb.

“I can see she’s been sick,” said a newly-arrived grey-haired woman who seemed to be in charge of the uniformed ones.

“All over this nice new dress,” said the first aider. “And banging her face on the floor didn’t do her much good.”

“She fell,” said the fat woman.

“I’ve fixed the cut,” said the first aider. “Might leave a bit of a scar.”

“A scar?” asked Luke.

“Only a bit of a scar,” said the grey-haired woman.

“I’m sure,” said Luke, “the security ladies were not to blame.”

“To blame?” said the grey-haired woman. “I don’t see how my staff can be to blame.”

“I imagine they’re overworked,” said Luke, “what with the general rise in crime, especially shoplifting. We all make mistakes in the heat of the moment.” He glanced back at the first aider. “Will she need an ambulance?”

“She needs a good sleep more than anything.”

“Are you with her?” asked the grey-haired woman.

“Oh yes,” said Luke, “and yes, I can take her home. I think it would be safer for all of us if we followed the medical advice.”

“Will you be taking the dress?” asked the grey-haired woman, and handed it to him.

Luke took out his debit card.

In the Clio he said: “That was a fine mess!”

She clicked her fingers. “Laurel and Hardy! Ask me another.” She was giggly now and pressed up against him, her head on his shoulder. She smelled of vomit.

“There’s no help for it. I shall have to take you home. Sit up straight. You’ll have to navigate.”

“Oooh!” She sat up and smoothed her skirt. “Keiron might be home. You’ll be able to meet him.”

Oh God! thought Luke.

But God was on his side. No Keiron. Jayne’s front door was polished oak with frosted glass. She scrabbled in her handbag, eventually finding her key. Luke turned it in the lock first go.

“No, I’m not coming in. I want you to take a bath and go to bed.”

“Do I have to do all that alone?” She giggled again.

“Yes.” He wished he could think of a clever reply.

Her e-mail said: Who’s a brave hero then, rescuing little Jaynie? Kiss, kiss, kiss. Mmmm. Kiss again. Kiss again. Kiss again. He pressed delete so hard that his finger was sore for several minutes.

Next morning he sat in his office at the university. He typed his first e-mail to Jayne. He had thought hard about the dangers of this: of the e-mail turning up in the detritus of the university communications system and being discovered by a third party. But it was not as dangerous as typing at home where it might be seen by Marianne. In any case, there was no protection against the CID or MI5 or anyone else in this age of unremitting technology, if they put their minds to it.

And it was better to e-mail Jayne than to see her again. Ever. It wasn’t just the thought of Marianne finding out, though that was scary. He realised now that Jayne was… well, dangerous. He could think of no other word.

He typed: Jayne

Then he thought: was the name by itself too curt, too unemotional, too coldblooded? After all, they had been close these past few weeks. But no, it was the right mood to catch.

After more thought, he typed: I think it would be wrong for us to develop our relationship any further than

Any further than what? There ought to be a phrase which could be interpreted innocently, implying he was a pleasant young man politely rebuffing the overtures of an older woman with personality problems. The phone rang. He picked it up.

“Luke Birch?”

The voice was a man’s, and Luke knew straightaway who it was. “Yes,” he said.

“This is Professor Cannadine. I’d like to see you right away. I’m at home. I believe you already know the address.”

On his way out, Luke looked into Phil’s office. “I’m going to see Professor Cannadine.”

Phil looked up, smiled. “So. The poetry therapy project is coming along OK, then?”

The man who let him in was big, broad-shouldered, with long hair and a moustache. He looked like Rembrandt. He said: “She tried to kill herself.”

Luke was relieved he hadn’t sent the e-mail; at least he couldn’t be blamed. He followed Rembrandt upstairs.

Jayne was sitting up in a four-poster bed wearing a white frilly nightdress with a high neckline – surprisingly modest, thought Luke, but indicative of the seriousness of the situation. “Hello, Lukey,” she said and smiled, showing her wonderful teeth, and waving an arm with a bandaged wrist.

“She cut both of them,” said Rembrandt. “Show him the other one, Jayne.”

Jayne waved the other arm. “I’ve been a silly girl.”

“Yes, you have,” said Rembrandt.

“Whatever,” said Jayne.

Rembrandt said: “Have you got your book?”

“Oh yes.” She picked up a hardback copy of Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter from beneath her pillow. “A book is a great comfort in times of stress. Don’t you find that, Luke?”

“Come on,” said Rembrandt and they went downstairs. “It’s not the first time she’s done this. Or taken pills. Or run the car into a gatepost. And it won’t be the last. It won’t be the last until it is the last, if you take my meaning. And it’s not the first time I’ve had to deal with somebody like you ending up on my doorstep. So forgive me if I don’t offer you a cup of coffee. But I’m all out of energy and goodwill right now.” He paused, breathless. “I thought you’d better see her. I thought she owed you that.” He opened the front door.

“She’s not reading it in French,” said Luke.

“Reading what?”

“Simone de Beauvoir.”

“She can’t read French.”

“I bet she can’t speak it either.”

“You’d win your bet.”

“And her mother is English and she’s still alive.”

“She’s Welsh. And she was getting along OK when we visited last month.”

“And – I don’t know quite how to put this. You’re not gay, are you?”

Rembrandt raised an eyebrow.

“No. OK. Right,” said Luke. “Thanks. Well, I hope she gets well. I mean soon.” He got in the Clio and drove away.

WHEN HE got home that night, he knew something was wrong. He could hear it: Marianne in the kitchen sobbing. He ran to her. “Lover,” he said, “sweetheart, what’s…?” He put his arms round her but she pulled away. Her office clothes were unchanged, her face buried in a Kleenex, a box of them on the table. She turned to face him.

“An affair!” she shouted. “How could anybody do it? Anybody who was happily married?”

He felt the cold run through his body. He began to say sorry but the word was strangled in his throat.

“Well,” she went on, “I’ll tell you why I did it, Luke! Because I’m not happily married! I used to be, but all that changed! You changed it! I hardly see you these days. Well, now I’m seeing someone else.”

It hit him like a sharp stomach ache. “Andy!” He sat down on the nearest chair.

“You must have seen the signs. But you just didn’t care.” She paused. “He’s offered me a partnership.”

“Andy,” Luke said again.

“And when I do see you, we never talk. Not about important things. I am a woman, after all. I have….”

“Emotional needs.” He put his head in his hands.

“Yes, if you want to put it that way. And now I’m leaving you. I’ve spent the last two hours packing. My stuff is in my car. But I couldn’t just walk away without telling you. Face to face.”

He thought: Tough decision. Fast action. Deliver the blow. He looked up. “Of course not.”

“That would have been cowardly.”

“Right.”

She put on her coat. She said: “There’s still lots of stuff I need to come back for. And then we’ll have to get the lawyers in.”

“Lawyers.” He nodded.

“I hope you won’t be changing the locks. Or anything like that.”

“No. Nothing like that.” He lifted his hands in surrender.

Then she was gone.

He checked the bedroom. Her side of the wardrobe was empty, but at least she hadn’t cut up his Ben Reid shirts in a fit of rage. But then why should she? He was the injured party. She’d emptied her knicker drawer; taken shampoo, make-up remover, electric toothbrush and a few more intimate items from the bathroom; removed some books from the lounge – two Maeve Binchys and a Bridget Jones. Did he still love her? If she asked forgiveness, would he take her back? He sat on the kitchen floor for a quarter of an hour. Then he went upstairs to the office, switched on the computer.

He typed: Jayne, I learned a big lesson today. We all have emotional needs. Can we get together again next Tuesday or the Tuesday after? That’s if your wrists are better, of course.